A for Amitabh: Games and Tools for Empowerment by Thoughtshop Foundation

This piece first appeared in Take on Art, Design Issue in January 2012, and was guest edited by Mayank Mansingh Kaul.

Thoughtshop Foundation is a Social Communication Organisation. It is dedicated to creating new and effective ways of dealing with social issues, with the aim to educate, motivate and initiate change. Thoughtshop Foundation is headed by Himalini Varma and Satayan Sengupta.

Children discuss cards from a Thoughtshop Toolkit.

How does one ‘teach’ a nine year old who has already survived some of life’s harshest lessons?

How does one take sessions on sex education in a village community with young girls who have never been to school?

How does one train non-literate women in business management skills, or talk about ending domestic violence with groups of men and women who believe it’s a normal way of life?

These are just some of the questions we have had to ask ourselves, and our journey to find answers have spanned two decades of work with grass-root communities, across different corners of India and several other developing countries. The discoveries along the way have helped us build a philosophy and understand the nature of communications in a context where the written word is not recognised, and the issues to be raised are often considered taboo.

At its simplest, Communication Design for the social sector can be intended to provide information, or raise awareness. Sometimes, it aims to create behavioural change. But the real magic happens when communication design sparks off a dialogue that leads to a process of self reflection, empowerment and transformation, for an individual and a society.

Communicating rice cultivation, from seed to crop, in Jharkhand.

Lessons from Street Kids

One of our first experiences with working children on the streets of Delhi taught us that the communication process had to be learner centred – a ‘partnership’ – we had as much to learn from the children as we had to offer them. For these children (shoe shine boys, coolies and rag pickers), the street was their classroom, and life on the street was their living school; teaching them harsh, new lessons everyday. At the age of nine and ten years, they led independent adult lives and had already seen a great deal. They would not attend a mainstream school and they were not interested in alphabet books talking of apples and balls. Sessions would take place on the pavements, and children would rush off the moment they saw a potential customer who needed his shoes polished.

Life on the street had made them hide away their vulnerabilities and we needed ways to build trust and get beneath the hardened exterior, find the little child inside. We needed to find a way to excite and connect with the children; help them share their personal stories, learn from them and move ahead. The idea was to appear like a magician before the kids with a bag full of tricks to capture their hearts and minds. After spending many weeks with the children, we developed a kit of games for them. One of the tools, for example, was a set of 36 brightly coloured picture cards; a series of images that captured different moments, emotions, choices and milestones in the children’s’ life.

When asked direct questions about their life, children would withdraw. Yet when playing with the picture cards they would open up. They would pick out cards with situations that they had experienced, and the stories they wove around them were real experiences. This would form an important foundation for further interactions with them. The cards would also serve as a tool to help the children express their feelings, and aspirations. Many cards were open – ended and could be interpreted in different ways.

One card for example had a picture of a boy sitting, looking thoughtful, and a little sad. ‘This boy is sad because he has just lost his shoeshine box and he is wondering what to do now. Since someone stole his box, should he steal someone else’s?’ Asked one. Another kid pulled out a card of a policeman hauling up a child: ‘If he steals a shoe box, then this is what will happen, and he will still be unhappy’. Another child pitched in: ‘I think the boy is sad because he is new and has no friends’, to which the other children agreed and shared how vulnerable a child feels when he is new and alone in the big city. And so, cards helped us learn about what was going on in the children’s minds. Actions and their consequences, social problems relevant to the children’s lives could now be addressed.

During the weeks we spent with the children we discovered that many of them were crazy about Bollywood films. They collected and traded pictures of famous stars. Inspired by this we developed a set of playing cards teaching the alphabet using film stars and famous personalities. So instead of learning A for Apple the children would learn A is for Amitabh (Bachhan)…

Family Spacing Board Game. Part of the Shankar Kit which addresses adolescent boys and young men.

Taboo!

It was 1996. We were travelling to a village group in South 24 Paragnas, West Bengal accompanied by Banidi, an elderly health worker with 21 years experience of working with communities. She complained to us about her latest predicament. She had been instructed to take sessions on reproductive health with girls – adolescents – young enough to be her granddaughters. She fished out a crumpled sheet of paper from a tin trunk, on which was typed a list of topics that she was expected to educate the girls on: Puberty, Menstruation, Conception, Sex Determination, Family Planning. She admitted to us that she had somehow never got around to discussing these issues with girls; it never felt like the right time she said. When we nodded in empathy, she confided how she felt this new requirement was quite unnecessary. She had always gone beyond the call of duty, but said she also had her self respect to consider. ‘What would the village elders think? Talking about sex to teenaged girls in a village’!!

Soon the young girls poured into the room, some looked as young as 12 years old, others may have been as old as 16. Most of these girls cannot read. They have never been to school or have dropped out so long ago that they remembered nothing. ‘How will they ever understand all this technical reproductive health stuff’! Banidi muttered to us under her breath. Later, when we asked the girls if they knew about how their body worked – about body systems – they looked completely blank. One of the girls mentioned that periodically a doctor visited their village and would give a lecture on such things. But they never really understood what she said and were too scared to ask. Marriage, children and motherhood, however, were round the corner; a reality that most of these girls would face most likely before their 18th birthday.

The Champa kit, a teaching aid for health workers disseminating information on reproductive health to rural adolescent girls.

The year long interactive development process resulted in the creation of a graded 5 module educational package of stories, games and models to discuss reproductive health with adolescent girls. Through the story of 12 year old Champa and her friends, different issues around reproductive health were raised. These stories were illustrated using lucid water colour paintings that were widely understood, and allowed the girls to let their imaginations flow. To break the ice and bridge the facilitator-learner divide, a card game showing social situations was introduced where the girls played as teams and challenged, argued and convinced each other on how different social situations influenced their lives. Games and models were developed to reduce the inhibitions around biological concepts of menstruation, conception, sex determination and the use of contraceptives. Games and activities were also devised to build life skills like assertiveness and negotiation.

Illustration from Champa’s discovery, Why does menstruation happen?, a flipchart from the Champa Kit.

Over the last 19 years the kit has been adapted in various languages and used by peer educators across the country to discuss reproductive health in a way that was non-threatening and fun! The interactive process enabled barefoot facilitators or peer educators (marginalised girls from the community) to replace resource persons as they started conducting free and open sessions to discuss sensitive issues. Young girls could freely share their questions with these didis who were most often just like them.

Now multiply that by a Million!

In 2006 we were lucky to be involved in a South Asia wide campaign to end violence against women. It was an ambitious campaign reaching out to 5 million individuals over 6 years and across 6 countries inspiring them to become change makers. Our role involved creating campaign communication, and youth change-makers in West Bengal.

The audience was diverse in every way. In India alone there were 13 states using over 8 languages. The campaign communication was driven by a set of guiding principles: Communication would be positive and inspiring, encourage personal change, be non- judgmental and challenge stereotypes, enable dialogue and be rights- based. And of course they would have to be pictorial and interactive. Through an intense process that covered several years, many participatory workshops and lots of help from partner organisations, we worked to develop a common pictorial language around the issue of gender and violence against women. This new language would have to cut across region, class, age and language barriers, not only within India, but across the campaign countries.

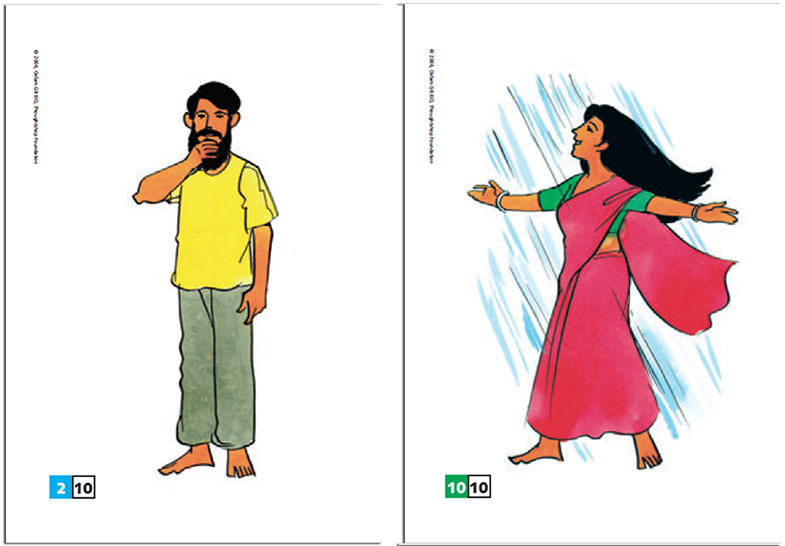

Character illustrations from the Understanding Gender and Violence against Women Toolkit.

One of the thumb rules of creating an image was this – the viewer must be able to imagine himself or herself as being the character in the image. This simple but very effective technique helped us maintain the dignity of characters, and therefore connect with men and women. It was interesting to hear people point out to images and say ‘I feel I am that man. I used to abuse my wife. I never thought it hurt her. I feel it now, I need to make a change’. The focus was on change – encouraging every individual to commit to even a small change; to believe that small efforts lead to big changes. There was also a continuous effort to find techniques that would challenge people’s beliefs, make them rethink attitudes that had been accepted without question for generations.

Here’s an example of an activity that elicited an interesting and familiar pattern of responses:

We would first show an image, of a woman doing the cooking and managing kids and her husband relaxing in the background, smoking a cigarette. People would respond casually saying that this is normal, this is how it is, how it has always been. Then we would show the same picture with the man doing the cooking and managing kids, while the wife is shown relaxing in the background smoking. At this, people would get startled. They would laugh nervously. “There must be some mistake. This is absurd…What a selfish woman!” And thus a raging discussion would begin.

New images and new scenarios were created to help people envision new realities where men shared housework, where women participated in decision- making. Many years later when an intensive impact assessment process was conducted and people were asked what they recalled, they would share powerful personal changes they have made in their life. They would often refer to the workshops as a series of images, which brought home to us the power of images to infuse into people’s consciousness.

One woman recalled the images of a woman eating less, being married early – ‘Those felt like pictures from my life…I wondered how the facilitators knew…Till then it never occurred to me this could change’!

At another interview, a father regretted that he had made a terrible mistake by forcing his under-age daughter to marry against her will. He would not repeat the same mistake with his younger girl. She would have the same freedom as Meenu, one of the characters in the communications.

The We Can Campaign to End Violence Against Women, with its focus on personal change and positive approach has now spread to 15 countries across the world, though the guiding principles remain the same. We have been privileged to work with teams from these other regions, to help them adapt the campaign strategy to their contexts.

Take-home picture and activity booklet for the participants of the My Childhood My Rights workshops.

Communication is Community Building

In our journey over these last two decades, our work has expanded to cover a wide range of issues: from self-exploration, exploring multiple identities, to child rights, water and sanitation, to poor women’s economic leadership and strategies for emergency relief. The solutions range from games and models to films, audio tools and multimedia. Training of trainers, especially grass-root facilitators or peer educators are integral processes. More recently our work could be better described as programme design: Creating sustainable, replicable models for development. Over the last few years, on our own initiative we have been creating community based youth leaders who do a journey from self to society, build youth groups and initiate positive social change within their communities.

It has been an amazing ride, as we have discovered the synergy between development communications and community building. Effective communication improves the quality of life and relationships between people. It increases empathy, reduces judgment and the barriers of misunderstanding that separate us from each other.

More information and materials for use are available at Thoughtshop Foundation’s website, facebook page and on twitter.

All images courtesy Thoughtshop Foundation